SpaceX SFR: The Small Falcon Rocket

Oct 18, 2017 17:02:39 GMT

SevenOfCarina, samchiu2000, and 2 more like this

Post by matterbeam on Oct 18, 2017 17:02:39 GMT

Hello! I think my latest blog post will interest you: toughsf.blogspot.com/2017/10/spacex-sfr-small-falcon-rocket.html

Here is the text with only original images:

SpaceX SFR: Small Falcon Rocket

The Small Falcon Rocket is a scaled down alternative to SpaceX's Big Falcon Spaceship that fits on top of existing Falcon 9 boosters.

We will discuss the advantages and disadvantages of such a design.

SpaceX's Big Rockets

The BFR, or Big Falcon Rocket, is comprised of the Big Falcon Spaceship and the Big Falcon Rocket booster. It is a scaled down and simplified design based on the ITS, or Interplanetary Transport System.

The ITS was revealed in June 2016, although work on the design has begun in 2013 under the name 'Mars Colonial Transporter'. The ITS promised to deliver 300 tons of cargo to Low Earth Orbit, or up to 550 tons if reusability was ignored. It would have massed 10500 tons on the launchpad. The vehicle had a diameter of 12 meters and a height of 122 meters, making it one of the largest rockets ever plausibly considered.

The upper stage, called the Interplanetary Spaceship, was supposed to hold 1950 tons of propellant with a dry mass of 150 tons. Without a payload, the mass ratio was 14.

The BFR replaced the ITS in September 2017. It is a smaller, more sensible design that SpaceX believes it can actually deliver in the next few years. The diameter is reduced to 9 meters and it will mass 4400 tons on the launchpad. Payload capacity is reduced to 150 tons.

The upper stage BFS should have a dry mass of 75 tons, but Elon Musk states that this might rise to 85 tons due to development bloat and overruns. It holds 1100 tons of propellant, giving it a mass ratio of 13.9.

It is important to note that despite being up to 78% smaller than the previous ITS design, the BFS stage maintains the same mass ratio. Why? Because we are now going to scale down the BFS again.

Why go smaller?

How big the BFR's booster would be compared to the Falcon 9 booster.

Going big is the best way to reduce the cost per kilogram for sending payloads into orbit. SpaceX jumped from the Falcon 1 to the Falcon 9 because the larger rocket can deliver payloads much more cheaply into space. When first considering options on how to make travel to Mars affordable to the general population, SpaceX immediately came up with a gargantuan tower of rocket fuel over three and a half times larger than the Saturn V!

A big rocket is also easier to develop. It is more forgiving of development bloat that increases mass over time as the designs are perfected. It has larger safety margins and room for many backups, such as multiple engines.

However, bigger is not always better.

The total development costs will be higher, as large components need large factories. It is much more difficult to test the components too, and a full testing regime of the completed rocket will require launching and even destroying a full-scale model many times. Remember the failed Falcon 9 booster landing attempts, and imagine them replaced with a vehicle eight times bigger.

There is also the fact that the second sure-fire way to reducing launch costs is to have rapid turnover. This involves loading up rockets, sending payloads into space, recovering the rocket and refurbishing it for another launch in a very small time frame, measured in days or even hours. Rapid turnover and minimal refurbishment would allow the space launch industry to more closely resemble existing airline business models. The main benefit of this approach is that a small number of launch vehicles can handle a large volume of missions, critically reducing the initial cost of the vehicles and reducing the amortization rate.

Even if SpaceX manages to develop rockets that liftoff and land several times without needing to go to a workshop, they'd still need to solve the issue that there just aren't enough payloads on the market that need to be lifted into space to fill the BFR, let alone the ITS.

For example, even the BFR's 150 ton payload capacity can cover all of last year's payloads in about two or three launches. Three launches is far from sufficient. Elon Musk is betting that the space industry will be able to fill the BFR's cargo bays with new satellites and LEO payloads once the lowered cost per kg is offered to them... but there will be a long delay between the launch costs being reduced and the industry contracts appearing en masse.

Waiting for more contracts to appear and bundling them together to use the most of a BFR's cargo capacity is not a good solution. It will force SpaceX to delay launches until the mass delivered to orbit reaches a profitable amount - launching BFRs nearly empty with the usual 2 to 5 ton satellite is surely wasteful and a loss for the company.

The SFR

The SFR, or Small Falcon Rocket, is a possible solution to the development costs, under-utilization and low expected launch rate of the BFR, or Big Falcon Rocket.

The SFR is a scaled down Big Falcon Spaceship sitting on top of an existing Falcon 9 booster. It will carry a smaller payload to orbit, but will have a capacity SpaceX is sure to fill up. Existing Falcon 9 boosters can be mated to a fully reusable upper stage, drastically cutting down on development costs.

We will now look at the details of the SFR's two stages.

The upper stage is the only new part. It is a BFS scaled down to 3.7 meters diameter, using the same Raptor engines rated at 1900kN of thrust at 375 seconds of Isp. We will call it the SFS, or Small Falcon Spaceship.

The SFS will be (9/3.7)^2: 5.9 times smaller than the BFS. The dry mass is expected to be only 85/5.9: 14.4 tons. It will be 19.7 meters long.

Based on the mass ratios calculated above, the SFS will be able to hold 187.2 tons of propellant. An SFS with no cargo and full propellant tanks will therefore mass 201.6 tons and have a deltaV of ln(14)*375*9.81: 9708m/s. The Vacuum-optimized Raptor engine is quite large, with a nozzle opening 2.4 meters wide. It is unlikely that more than one such engine can be fitted under the SFS. It will provide enough thrust for an initial Thrust-to-Weight ratio of 0.96, which must be compared to the current second-stage initial TWRs of 0.8-0.9. For retro-propulsive landing, we will not be able to fit, or even need, the sea-level version of the Raptors. Instead, we will use two of the existing Merlin-1D engines with 420kN of sea-level thrust, but possibly with a lower pressure rating as the thrust generated makes them too powerful for landing. The alternative is the SuperDraco engines with 67kN of thrust and 235s sea-level Isp.

Rocket engines in the Raptor + 2x Merlin configuration would represent 13.2% of the overall dry mass, or 8.1% if the Raptor + 4x SuperDraco configuration is used instead. The Raptor engines are assumed to have a TWR of over 200, so their mass should be lower than 969kg. There are no numbers on the SuperDraco's mass, but it should be at most 50kg. These ratios seem not too outrageous when compared to the 7% engine-mass-to-dry-mass ratio in the BFR's original design.

The SFS's mass is based on the 85 ton figure for the BFR's dry mass, but this is a cautious estimate with room given for development bloat and mass budget overruns. The BFR's design on paper gives a dry mass of 75 tons instead. Using the on-paper mass, the SFS could have a dry mass as little as 12.7 tons.

The SFR's booster is the Falcon 9 Block 4. The booster will mass 22.2 tons when empty, and can hold 410.9 tons of propellant. This gives it a mass ratio of 19.5. The nine Merlin 1D engines have a sea-level Isp of 282s and an vacuum Isp of 311s. Because the booster stage does not spend a long time at sea level and performs most of the burn at high altitudes with negligible air pressure, we will use 300s as a low-ball estimate of the average Isp. The true average might be a few seconds higher.

Taken all together, the SFR will mass 634.7 tons on the launchpad without any payload in the SFS's cargo bays. It stands 89.7 meters tall.

We will now calculate how much cargo it can lift into Low Earth Orbit in expendable or reusable mode, and where else it can go.

Performance

To achieve a Low Earth Orbit, we will set the deltaV requirement as 9400m/s. In reality, it could be achieved with as little as 9200m/s, but we want decent safety margins.

Expendable mode is the easy part. It assumes every bit of propellant is consumed and the SFR's stages left dry. Using a multi-stage deltaV calculator and setting the Falcon 9 Block 4's Isp to 300s and the SFS's Isp to 375s, we work out that the booster provides 1899m/s of deltaV and the SFS provides 7488m/s for a total of 9388m/s with a payload of 13.7 tons.

Recoverable mode is harder to calculate. The propellants cannot be completely used up: some must be kept in reserve to perform a retro-propulsive landing burn.

A landing burn by the SFS requires that about 300m/s of deltaV be held in reserve. This represents 1.65 tons of propellant with Merlin-1Ds or 2 tons of propellant with the SuperDracos.

The Falcon 9 booster needs to retain 15% of its propellant reserve to make an ocean landing. This gives it a deltaV of 3910m/s, which is largely enough to cancel most of its forwards velocity and make a very soft landing. However, holding back 61.6 tons of propellant means it boosts the SFS by much less.

In recoverable mode, the SFR's cargo capacity drops to 9 tons.

If the SFS follows the paper designs more closely and achieves a dry mass of 12.7 tons, it will have cargo capacities of 16.7 tons in expendable mode and 12 tons in recoverable mode.

The SFS could achieve a deltaV of 2500m/s after launching on top of a recoverable Falcon 9 booster and without any payload. This is not enough to reach the Moon, so the range of missions the SFR can take payloads on is limited to Low Earth Orbit.

Smaller rockets might solve the problem of having to crane down cargo from the top of a tower.

However, if it is refuelled in orbit, then the entire Solar System is available. It can deliver 50 tons to Low Lunar Orbit (5km/s mission deltaV). It can send 35 tons to the Mars Low Orbit (5.7km/s mission deltaV) or 21 tons to Mars's surface (6.7km/s mission deltaV). Refueling the SFS will take between 16 and 20 tanker launches.

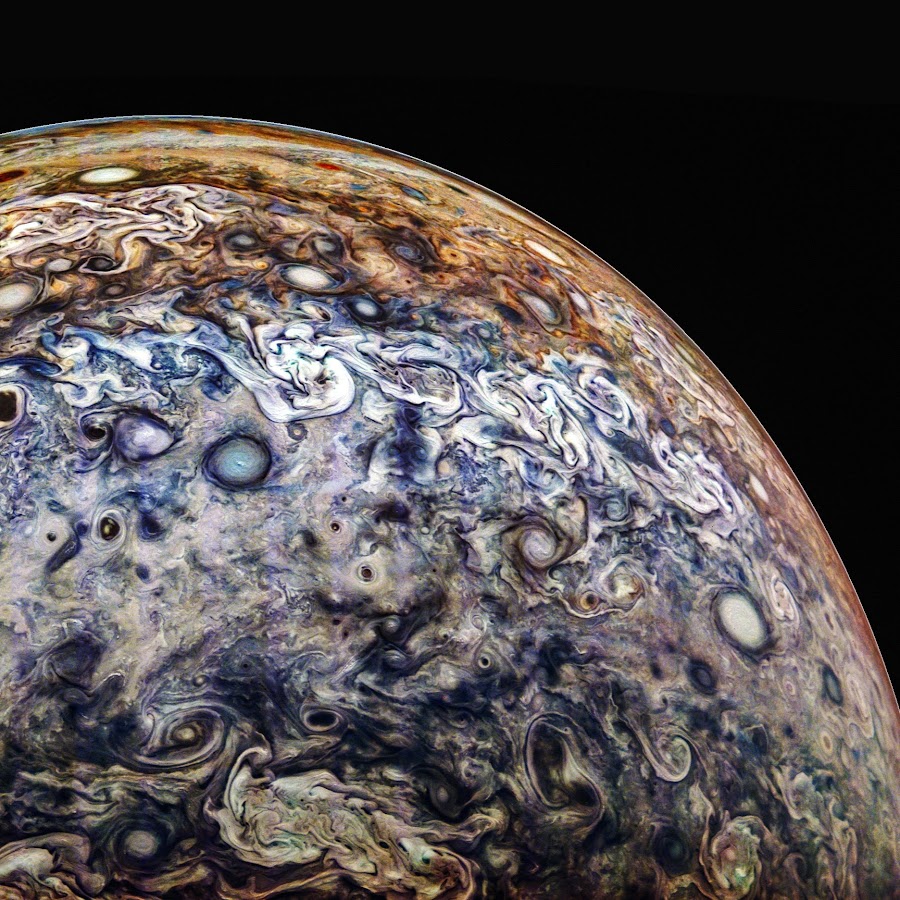

With 14.4 tons of dry mass and a propellant capacity of 187.2 tons, the SFS has a maximal deltaV of 9.7km/s, enough theoretically to put itself far above Jupiter or even Saturn.

Conclusions

The SFS is a limited vehicle. It is restricted to Low Earth Orbits and can deliver payloads of 9 tons, up to 12 tons, at most. It is far from the multi-purpose machines the BFR or ITS promised to be.

However, it is enough to dominate the medium lift launch market, as it is fully recoverable. The re-use of existing Falcon 9 boosters and the smaller number of Raptor engines (one per rocket) will drastically slash the development costs compared to something like the BFR. The smaller payloads are easy to fill, meaning every launch is profitable. Multiple launches promises rapid turnover and a maximization of the return on investment on the craft.

With re-fueling, the SFS in orbit can complete missions that require it to send decent payloads to the Moon and Mars. With minor improvements and operating in fleets of multiple vehicles, it can even match the payload capacity of the BFR to various destinations.

Here is the text with only original images:

SpaceX SFR: Small Falcon Rocket

We will discuss the advantages and disadvantages of such a design.

SpaceX's Big Rockets

The BFR, or Big Falcon Rocket, is comprised of the Big Falcon Spaceship and the Big Falcon Rocket booster. It is a scaled down and simplified design based on the ITS, or Interplanetary Transport System.

The ITS was revealed in June 2016, although work on the design has begun in 2013 under the name 'Mars Colonial Transporter'. The ITS promised to deliver 300 tons of cargo to Low Earth Orbit, or up to 550 tons if reusability was ignored. It would have massed 10500 tons on the launchpad. The vehicle had a diameter of 12 meters and a height of 122 meters, making it one of the largest rockets ever plausibly considered.

The upper stage, called the Interplanetary Spaceship, was supposed to hold 1950 tons of propellant with a dry mass of 150 tons. Without a payload, the mass ratio was 14.

The BFR replaced the ITS in September 2017. It is a smaller, more sensible design that SpaceX believes it can actually deliver in the next few years. The diameter is reduced to 9 meters and it will mass 4400 tons on the launchpad. Payload capacity is reduced to 150 tons.

The upper stage BFS should have a dry mass of 75 tons, but Elon Musk states that this might rise to 85 tons due to development bloat and overruns. It holds 1100 tons of propellant, giving it a mass ratio of 13.9.

It is important to note that despite being up to 78% smaller than the previous ITS design, the BFS stage maintains the same mass ratio. Why? Because we are now going to scale down the BFS again.

Why go smaller?

How big the BFR's booster would be compared to the Falcon 9 booster.

Going big is the best way to reduce the cost per kilogram for sending payloads into orbit. SpaceX jumped from the Falcon 1 to the Falcon 9 because the larger rocket can deliver payloads much more cheaply into space. When first considering options on how to make travel to Mars affordable to the general population, SpaceX immediately came up with a gargantuan tower of rocket fuel over three and a half times larger than the Saturn V!

A big rocket is also easier to develop. It is more forgiving of development bloat that increases mass over time as the designs are perfected. It has larger safety margins and room for many backups, such as multiple engines.

However, bigger is not always better.

The total development costs will be higher, as large components need large factories. It is much more difficult to test the components too, and a full testing regime of the completed rocket will require launching and even destroying a full-scale model many times. Remember the failed Falcon 9 booster landing attempts, and imagine them replaced with a vehicle eight times bigger.

There is also the fact that the second sure-fire way to reducing launch costs is to have rapid turnover. This involves loading up rockets, sending payloads into space, recovering the rocket and refurbishing it for another launch in a very small time frame, measured in days or even hours. Rapid turnover and minimal refurbishment would allow the space launch industry to more closely resemble existing airline business models. The main benefit of this approach is that a small number of launch vehicles can handle a large volume of missions, critically reducing the initial cost of the vehicles and reducing the amortization rate.

Even if SpaceX manages to develop rockets that liftoff and land several times without needing to go to a workshop, they'd still need to solve the issue that there just aren't enough payloads on the market that need to be lifted into space to fill the BFR, let alone the ITS.

For example, even the BFR's 150 ton payload capacity can cover all of last year's payloads in about two or three launches. Three launches is far from sufficient. Elon Musk is betting that the space industry will be able to fill the BFR's cargo bays with new satellites and LEO payloads once the lowered cost per kg is offered to them... but there will be a long delay between the launch costs being reduced and the industry contracts appearing en masse.

Waiting for more contracts to appear and bundling them together to use the most of a BFR's cargo capacity is not a good solution. It will force SpaceX to delay launches until the mass delivered to orbit reaches a profitable amount - launching BFRs nearly empty with the usual 2 to 5 ton satellite is surely wasteful and a loss for the company.

The SFR

The SFR, or Small Falcon Rocket, is a possible solution to the development costs, under-utilization and low expected launch rate of the BFR, or Big Falcon Rocket.

We will now look at the details of the SFR's two stages.

The upper stage is the only new part. It is a BFS scaled down to 3.7 meters diameter, using the same Raptor engines rated at 1900kN of thrust at 375 seconds of Isp. We will call it the SFS, or Small Falcon Spaceship.

The SFS will be (9/3.7)^2: 5.9 times smaller than the BFS. The dry mass is expected to be only 85/5.9: 14.4 tons. It will be 19.7 meters long.

Based on the mass ratios calculated above, the SFS will be able to hold 187.2 tons of propellant. An SFS with no cargo and full propellant tanks will therefore mass 201.6 tons and have a deltaV of ln(14)*375*9.81: 9708m/s. The Vacuum-optimized Raptor engine is quite large, with a nozzle opening 2.4 meters wide. It is unlikely that more than one such engine can be fitted under the SFS. It will provide enough thrust for an initial Thrust-to-Weight ratio of 0.96, which must be compared to the current second-stage initial TWRs of 0.8-0.9. For retro-propulsive landing, we will not be able to fit, or even need, the sea-level version of the Raptors. Instead, we will use two of the existing Merlin-1D engines with 420kN of sea-level thrust, but possibly with a lower pressure rating as the thrust generated makes them too powerful for landing. The alternative is the SuperDraco engines with 67kN of thrust and 235s sea-level Isp.

Rocket engines in the Raptor + 2x Merlin configuration would represent 13.2% of the overall dry mass, or 8.1% if the Raptor + 4x SuperDraco configuration is used instead. The Raptor engines are assumed to have a TWR of over 200, so their mass should be lower than 969kg. There are no numbers on the SuperDraco's mass, but it should be at most 50kg. These ratios seem not too outrageous when compared to the 7% engine-mass-to-dry-mass ratio in the BFR's original design.

The SFS's mass is based on the 85 ton figure for the BFR's dry mass, but this is a cautious estimate with room given for development bloat and mass budget overruns. The BFR's design on paper gives a dry mass of 75 tons instead. Using the on-paper mass, the SFS could have a dry mass as little as 12.7 tons.

The SFR's booster is the Falcon 9 Block 4. The booster will mass 22.2 tons when empty, and can hold 410.9 tons of propellant. This gives it a mass ratio of 19.5. The nine Merlin 1D engines have a sea-level Isp of 282s and an vacuum Isp of 311s. Because the booster stage does not spend a long time at sea level and performs most of the burn at high altitudes with negligible air pressure, we will use 300s as a low-ball estimate of the average Isp. The true average might be a few seconds higher.

Taken all together, the SFR will mass 634.7 tons on the launchpad without any payload in the SFS's cargo bays. It stands 89.7 meters tall.

We will now calculate how much cargo it can lift into Low Earth Orbit in expendable or reusable mode, and where else it can go.

Performance

To achieve a Low Earth Orbit, we will set the deltaV requirement as 9400m/s. In reality, it could be achieved with as little as 9200m/s, but we want decent safety margins.

Expendable mode is the easy part. It assumes every bit of propellant is consumed and the SFR's stages left dry. Using a multi-stage deltaV calculator and setting the Falcon 9 Block 4's Isp to 300s and the SFS's Isp to 375s, we work out that the booster provides 1899m/s of deltaV and the SFS provides 7488m/s for a total of 9388m/s with a payload of 13.7 tons.

Recoverable mode is harder to calculate. The propellants cannot be completely used up: some must be kept in reserve to perform a retro-propulsive landing burn.

A landing burn by the SFS requires that about 300m/s of deltaV be held in reserve. This represents 1.65 tons of propellant with Merlin-1Ds or 2 tons of propellant with the SuperDracos.

The Falcon 9 booster needs to retain 15% of its propellant reserve to make an ocean landing. This gives it a deltaV of 3910m/s, which is largely enough to cancel most of its forwards velocity and make a very soft landing. However, holding back 61.6 tons of propellant means it boosts the SFS by much less.

In recoverable mode, the SFR's cargo capacity drops to 9 tons.

If the SFS follows the paper designs more closely and achieves a dry mass of 12.7 tons, it will have cargo capacities of 16.7 tons in expendable mode and 12 tons in recoverable mode.

The SFS could achieve a deltaV of 2500m/s after launching on top of a recoverable Falcon 9 booster and without any payload. This is not enough to reach the Moon, so the range of missions the SFR can take payloads on is limited to Low Earth Orbit.

Smaller rockets might solve the problem of having to crane down cargo from the top of a tower.

However, if it is refuelled in orbit, then the entire Solar System is available. It can deliver 50 tons to Low Lunar Orbit (5km/s mission deltaV). It can send 35 tons to the Mars Low Orbit (5.7km/s mission deltaV) or 21 tons to Mars's surface (6.7km/s mission deltaV). Refueling the SFS will take between 16 and 20 tanker launches.

With 14.4 tons of dry mass and a propellant capacity of 187.2 tons, the SFS has a maximal deltaV of 9.7km/s, enough theoretically to put itself far above Jupiter or even Saturn.

Conclusions

The SFS is a limited vehicle. It is restricted to Low Earth Orbits and can deliver payloads of 9 tons, up to 12 tons, at most. It is far from the multi-purpose machines the BFR or ITS promised to be.

However, it is enough to dominate the medium lift launch market, as it is fully recoverable. The re-use of existing Falcon 9 boosters and the smaller number of Raptor engines (one per rocket) will drastically slash the development costs compared to something like the BFR. The smaller payloads are easy to fill, meaning every launch is profitable. Multiple launches promises rapid turnover and a maximization of the return on investment on the craft.

With re-fueling, the SFS in orbit can complete missions that require it to send decent payloads to the Moon and Mars. With minor improvements and operating in fleets of multiple vehicles, it can even match the payload capacity of the BFR to various destinations.